The oft cited metaphor of the ocean

beautifully describes the paradox of continuity and individuality that we create

when we first emerge from the source of all life and think "I

AM."

Through this metaphor we can imagine how the source of the ocean runs deep and wide, but on its surface bursts forth individual sparkling waves that might, if they could, think of themselves as separate from each other. And, riding high on the cusp of a swell, believe themselves to also be separate from the deep waters below.

photo by GD Taber. Creative Commons License 2.0

This is similar to how each of us,

at the time of our birth, emerges from the source of all life (call it spirit,

consciousness, soul, God, or Nirvana) and we begin to think of ourselves as separate,

individual beings.

We think "I AM" and we no longer remember the

source from which we have all sprung. We think of ourselves as an individual and we look at each other as if separate.

We forget that we are one. And in this

way we enter what is referred to in Buddhism as the first of the Three Poisons: Ignorance.

Photo by George A. Piva. Creative Commons License 2.0

Ignorance is the state of mind that is unaware of itself.

Because we have forgotten that we

are one with the source, we assume that who we are is what we think. And we

think that our thoughts are the whole truth.

Through our thoughts, we continually

define and redefine ourselves, and variously construct our identities. We think

of ourselves as any number of the multitude of possible roles we can conceive

of, such as the roles we play with our families, occupations, and communities.

Likewise, we continually define and redefine the identities of others, just as others

create their own view of us while also constructing identities for

themselves.

These thoughts are so all-consuming, so all-encompassing, that we assume that these thoughts about ourselves and others are “true” reflections of who we are, who others are, and “true” explanations of our shared experience.

Photo by Taku. Creative Commons License 2.0

The other two poisons—grasping and aversion—arise out of our fear over the loss of our individuality.

Out of fear of letting go of the identities we've constructed for ourselves, we have an aversion to anything that challenges our sense of self—we avoid those things that do not reflect who we are. And, we grasp onto anything that supports our constructed identities. We surround ourselves with people, occupations, and possessions, and we think these things reflect who we are.

We see our choices as reflections of who we are:

An intellectual's library is a reflection of how well-read he is; A

child's good behavior reflects her parents' good parenting; An artist's home

has aesthetically pleasing objects that reflect her creativity. A student's circle of friends are a reflection of how smart, cool or athletic he is.

All suffering arises out of the Three Poisons, which are the states of mind known as ignorance, grasping and aversion.

The loss of a job or home, the end of a marriage, the onset of the “empty

nest,” even the occasion when someone we trust tells us we're wrong are all

examples of experiences that can trigger suffering within us because these thing threaten what we think about ourselves and we believe who we are is what we think.

Fortunately for us, every

single moment of our lives is rich with opportunity to develop an awareness of

the gap between our thoughts, which we assume are true, and the source which is always already within us, and which is the only truth.

Photo by Shiro169. Creative Commons License 2.0

Awareness can be awakened for anyone at any moment, and a simple practice that anyone can do is to witness the train of thoughts and feelings that arise within us during ordinary situations.

When we receive praise, for

instance, or face criticism, we can observe whether we relish the praise and

seek further acknowledgement, or whether we feel embarrassed and think we don’t deserve

it. We can take note if we feel shame or humiliation when criticized by others

or if we feel indignant and think our critics are just acting out of their own

jealousy or perfectionism.

And instead of assuming that the

narratives we create about our experiences are “true” and allowing such

thoughts to compound, we can just observe them and, should we choose to do so,

simply let them go.

Through this type of mindfulness, we can begin to observe "gaps" between who we think we are and the quiet, peaceful place within that is the silent witness to these thoughts. Eventually, the train of thoughts that once preoccupied the mind begins to become less frequent, and less insistent ... until the source that is always already within is unveiled.

When this happens, it's not that the source which was forgotten is now remembered; it's more like the source which was always known is now realized.

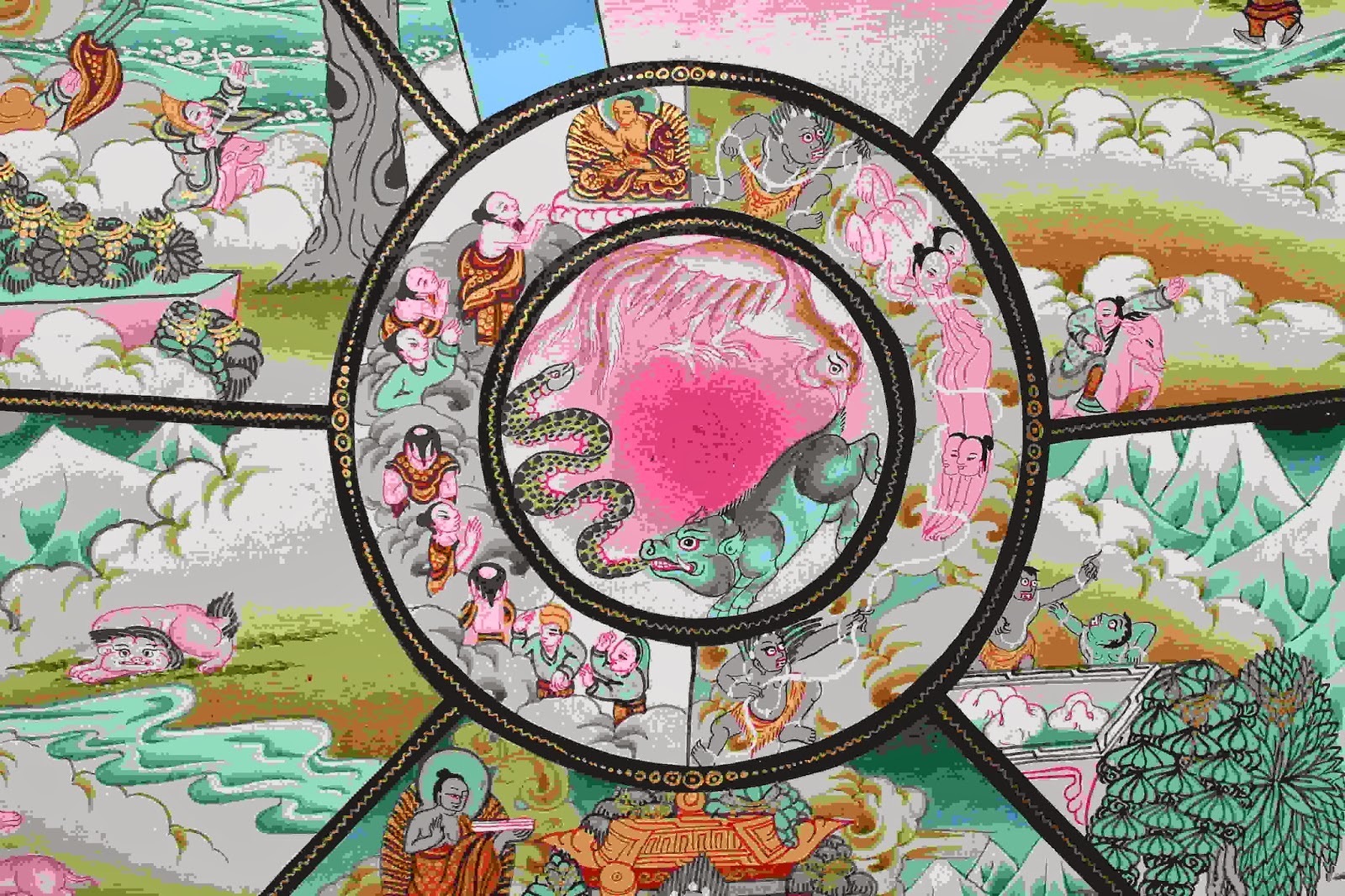

For further explanation

of these ideas please see "The Wheel of Life: A Brief Explanation"

in The Six Realms of Samsara: Stories for Awakening by Lindsey

Arnold. Now available on My Author's Spotlight . Please also see additional blogs below or above on this site or other of my blogs on A Guru Once Said. Thank you!

The oft cited metaphor of the ocean

beautifully describes the paradox of continuity and individuality that we create

when we first emerge from the source of all life and think "I

AM."

Through this metaphor we can imagine how the source of the ocean runs deep and wide, but on its surface bursts forth individual sparkling waves that might, if they could, think of themselves as separate from each other. And, riding high on the cusp of a swell, believe themselves to also be separate from the deep waters below.

|

| photo by GD Taber. Creative Commons License 2.0 |

This is similar to how each of us,

at the time of our birth, emerges from the source of all life (call it spirit,

consciousness, soul, God, or Nirvana) and we begin to think of ourselves as separate,

individual beings.

We think "I AM" and we no longer remember the

source from which we have all sprung. We think of ourselves as an individual and we look at each other as if separate.

We forget that we are one. And in this

way we enter what is referred to in Buddhism as the first of the Three Poisons: Ignorance.

|

| Photo by George A. Piva. Creative Commons License 2.0 |

Ignorance is the state of mind that is unaware of itself.

Because we have forgotten that we

are one with the source, we assume that who we are is what we think. And we

think that our thoughts are the whole truth.

Through our thoughts, we continually

define and redefine ourselves, and variously construct our identities. We think

of ourselves as any number of the multitude of possible roles we can conceive

of, such as the roles we play with our families, occupations, and communities.

Likewise, we continually define and redefine the identities of others, just as others

create their own view of us while also constructing identities for

themselves.

These thoughts are so all-consuming, so all-encompassing, that we assume that these thoughts about ourselves and others are “true” reflections of who we are, who others are, and “true” explanations of our shared experience.

|

| Photo by Taku. Creative Commons License 2.0 |

We see our choices as reflections of who we are:

An intellectual's library is a reflection of how well-read he is; A

child's good behavior reflects her parents' good parenting; An artist's home

has aesthetically pleasing objects that reflect her creativity. A student's circle of friends are a reflection of how smart, cool or athletic he is.

All suffering arises out of the Three Poisons, which are the states of mind known as ignorance, grasping and aversion.

The loss of a job or home, the end of a marriage, the onset of the “empty nest,” even the occasion when someone we trust tells us we're wrong are all examples of experiences that can trigger suffering within us because these thing threaten what we think about ourselves and we believe who we are is what we think.

Fortunately for us, every

single moment of our lives is rich with opportunity to develop an awareness of

the gap between our thoughts, which we assume are true, and the source which is always already within us, and which is the only truth.

|

| Photo by Shiro169. Creative Commons License 2.0 |

Awareness can be awakened for anyone at any moment, and a simple practice that anyone can do is to witness the train of thoughts and feelings that arise within us during ordinary situations.

When we receive praise, for

instance, or face criticism, we can observe whether we relish the praise and

seek further acknowledgement, or whether we feel embarrassed and think we don’t deserve

it. We can take note if we feel shame or humiliation when criticized by others

or if we feel indignant and think our critics are just acting out of their own

jealousy or perfectionism.

And instead of assuming that the

narratives we create about our experiences are “true” and allowing such

thoughts to compound, we can just observe them and, should we choose to do so,

simply let them go.

Through this type of mindfulness, we can begin to observe "gaps" between who we think we are and the quiet, peaceful place within that is the silent witness to these thoughts. Eventually, the train of thoughts that once preoccupied the mind begins to become less frequent, and less insistent ... until the source that is always already within is unveiled.

When this happens, it's not that the source which was forgotten is now remembered; it's more like the source which was always known is now realized.

For further explanation

of these ideas please see "The Wheel of Life: A Brief Explanation"

in The Six Realms of Samsara: Stories for Awakening by Lindsey

Arnold. Now available on My Author's Spotlight . Please also see additional blogs below or above on this site or other of my blogs on A Guru Once Said. Thank you!

%2Bflipped.jpg)

%2Bweb%2Bquality.jpg)